KEEPING THE HUMAN SPIRIT ALIVENov 4, 2025

KEEPING THE HUMAN SPIRIT ALIVENov 4, 2025English

Español

KEEPING THE HUMAN SPIRIT ALIVENov 4, 2025

KEEPING THE HUMAN SPIRIT ALIVENov 4, 2025

In the pantheon of twentieth-century European intellectuals, Pier Paolo Pasolini stands alone. He was a filmmaker, poet, philosopher, and provocateur. A Marxist who quoted scripture. A gay man who mourned lost innocence. A cultural critic who confronted modernity without apology. Beneath the polemics and controversy, however, lived a quieter Pasolini — one deeply, privately, and passionately in love with music.

Music, to Pasolini, was not an accessory. It was memory, resistance, and a form of truth. He turned to it not to escape but to preserve what he saw slipping away. His was not the love of performance or spectacle. It was the love of sound as soul.

His fascination with music began in Friuli, the rural region in northeastern Italy where he spent part of his youth. There, he encountered an oral culture built on dialect, tradition, and song. Folk music, for Pasolini, was not entertainment. It was a cry of identity. The melodies of peasants and laborers held something sacred. They were not crafted for the stage but born of lived experience. These were songs sung in fields, kitchens, and funerals. Long before the term “world music” entered the marketplace, Pasolini was recording these voices with care and urgency.

He believed these traditions were disappearing under the weight of consumerism and industrialization. Preserving them became an ethnographic exercise and a political act. Through his writing and field recordings, he sought to document not nostalgia but survival. The voices of the poor mattered. Their stories mattered. Their songs, too, deserved to be heard.

This philosophy carried into his films. In Accattone, his 1961 debut about a pimp surviving on the edges of Roman society, Pasolini paired gritty black-and-white realism with Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Critics were puzzled by the sacred soundtrack, but Pasolini’s choice was deliberate. He wanted to elevate the poor to the level of myth. Their suffering was real, and therefore it was holy.

In The Gospel According to Matthew, released in 1964, Pasolini blended European classical music with African liturgical chants and American gospel. This fusion was not an experiment in aesthetics. It was a political and spiritual vision. Christ, in Pasolini’s hands, was not a symbol of the Church but a figure of the people. The music gave him a global voice.

Pasolini did not admire music for its polish. He was drawn to the unpolished human voice. The imperfections in tone and rhythm moved him more than technical mastery ever could. He found beauty in the trembling note and the unresolved chord. He believed a voice revealed truth when it cracked.

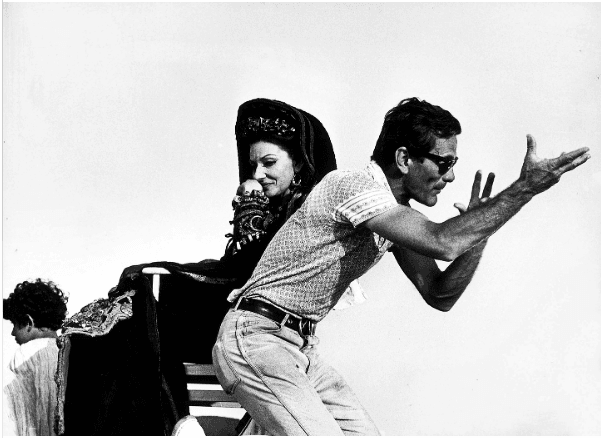

This sensibility explains his profound admiration for Maria Callas. He met the opera legend later in her life, when her voice no longer held the clarity it once had. That did not matter to him. Her voice, he believed, carried myth, pain, and memory. He cast her in Medea in 1969, even though she did not sing in the film. He wanted her presence, her silence, her tragedy. For Pasolini, she did not need music to be musical.

Their friendship was deep, intimate, and layered. It was not romantic, but undeniably tender. In Callas, Pasolini saw the embodiment of everything he loved in music: beauty shaped by suffering and control shaped by chaos.

Pasolini’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) offers another compelling glimpse into his musical vision. The film adapts Geoffrey Chaucer’s medieval stories with an earthy vibrancy that celebrates the raw and diverse voices of ordinary people. Pasolini enriched the narrative with folk-inspired music, echoing his earlier ethnographic interest in traditional sounds. The score, composed by the celebrated Ennio Morricone, weaves together rustic melodies and atmospheric textures that bring the medieval world to life—not as distant history, but as a living, breathing culture. Through music, Pasolini gives voice to a communal identity rooted in storytelling, human folly, and the timeless rhythms of life.

Pasolini was murdered in 1975 under violent and suspicious circumstances. The case remains controversial, and many believe he was targeted for his politics. His death, sudden and brutal, felt like the silencing of a unique cultural voice.

Yet his love for music continues to echo. It survives in his films, where sacred compositions accompany stories of poverty and faith. It lives in the recordings he made of voices that might otherwise have been lost. It lingers in his belief that music belongs not to elites but to everyone.

Pasolini did not simply hear music. He listened. He listened with urgency, reverence, and love. And through his work, we can still listen too.

References

*Ceccatty, René de. (2005). Pier Paolo Pasolini. Paris: Gallimard.

*Willson, Piers Paul. (1994). Pier Paolo Pasolini: Performing Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.